By Leah Agustin

1st Year Management Intern

The inextricable link between planetary health and public health has been spotlighted in the global climate change agenda, as the United Nations COP28 welcomed its first dedicated Health Day in December 2023 [1]. This day marked a crucial step in addressing health impacts from climate change. Australia launched its inaugural National Health and Climate Strategy [2] and formally signed up to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Alliance for Transformative Action on Climate and Health [3]. More notably, this day marked the COP28 UAE Declaration on Climate and Health. This represents a promising moment for climate action, with over 120 countries endorsing the Declaration and acknowledging the need to “place health at the heart of climate action” [4].

With all this in mind, I want to take the time to reflect on four key lessons I have learned to date.

#1 – The climate crisis is a public health crisis.

Climate change is recognised as the greatest public health threat in the 21st century, exacerbating health risks and health inequities across the globe. The latest 2023 Lancet Countdown report highlights the wide-ranging and rapidly increasing severity of climate change impacts on people’s health and well-being [5].

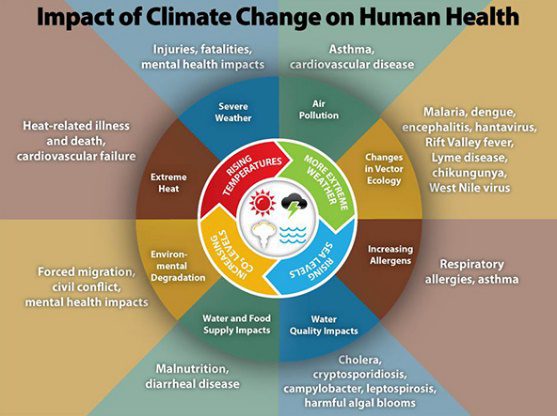

Climate change impacts on human health [6].

The analysis of global temperature records in the 2023 Lancet Countdown Report emphasizes the increasing health toll of climate change [5]. Heat-related deaths of older individuals aged over 65 years in 2020 have risen by 85% compared to 1990-2000, significantly higher than the expected 38% increase without anthropogenic climate change and global warming [5]. The year 2022 broke heat records across all continents, and the year 2023 had the highest global temperatures in over 100,000 years [5].

The message from the Lancet, WHO, and over 40 million health professionals at COP28, is clear. The climate crisis is a public health crisis. Climate inaction is costing people’s lives.

“We should not measure progress on the climate crisis just by the degrees averted but by the lives saved”. – US Specialist Climate Envoy John Kerry in COP28 [7].

#2 – Environmental sustainability and financial sustainability are not mutually exclusive.

There is no denying that a substantial financial investment is required to address climate change and deliver climate resilient, and low carbon health systems. However, it should be acknowledged that decision-makers should not have to trade-off financial sustainability for environmental sustainability. Climate change has resulted in significant global economic losses, with an estimated US $264 billion loss attributed to extreme weather events and US $863 billion potential income loss attributed to heat exposure [5]. Conversely, there are promising long-term financial benefits associated with investing in environmentally sustainable initiatives. The Australian National Health and Climate Strategy includes case studies from Royal Melbourne Hospital that highlight these financial and environmental co-benefits:

- Telehealth Program: Virtual appointments held between January and November 2022 avoided 12 million km of patient travel, equating to a 2.4kt CO2-e emissions reduction. This also minimised N95 masks depletion, equating to 6.7 tCO2-e emissions reduction and cost savings of about $154,000.

- Minimising Low Value Care in ED: An educational initiative carried out in 2022 avoided over 1200 unnecessary blood tests per month, equating to annual cost savings of $240,000 and 900kg CO2-e emissions reduction.

- Environmental Sustainability Competition: The collaborative implementation of clinical and non-clinical initiatives in 2022 resulted in 2.5 ktCO2-e emissions reduction and cost savings of $500,000 [2].

It is important that we debunk the myth of trade-off between environmental and financial goals, and instead, incorporate a holistic approach that foster health, environmental and economic well-being.

#3 – First Peoples’ voice must be at the centre of climate and health decision-making.

First Peoples leadership is essential to ensuring effective and equitable climate and health policy decision-making. As the Traditional Custodians of the land, seas, and waterways for over 60,000 years, First Peoples hold deep knowledge systems to effectively inform climate change mitigation and adaptation initiatives [2,8]. Moreover, colonisation and climate change exacerbate health inequities, greatly impacting the social and cultural determinants of health, especially for marginalised communities such as First Peoples [2,8]. It is therefore imperative that we centre the voice of First Peoples – to ensure sustainable and equitable policies and resource allocation.

“Healthy Country and healthy people go hand in hand”. Maddison Miller, Dharug woman and Lecturer in Ecology Knowledges, University of Melbourne [2].

#4 – Effective climate action requires intersectoral collaboration on a local, national, and global scale.

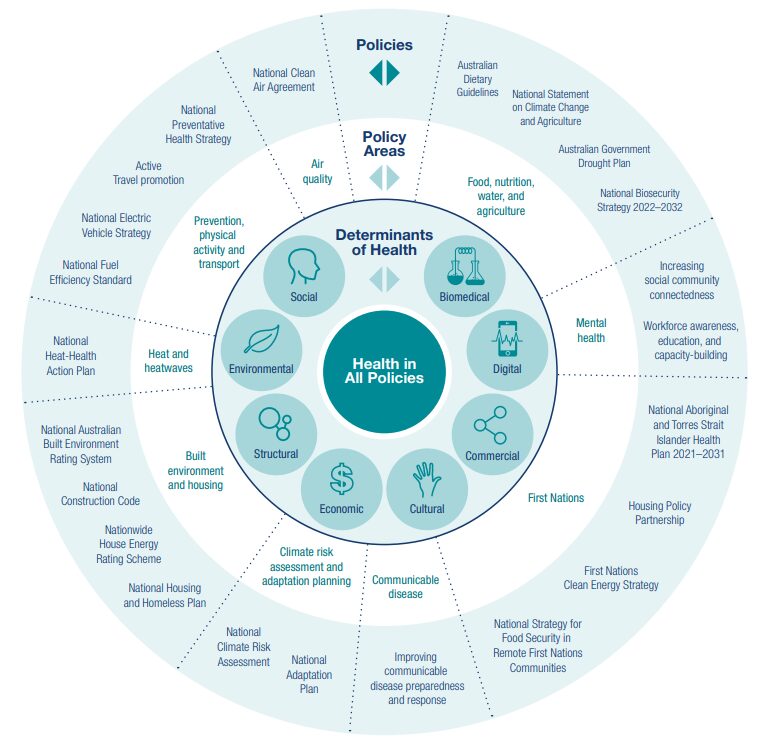

Much like solving any other wicked problems, effective climate action cannot be done in silos. The National Health and Climate Strategy adopts WHO’s Health in All Policies approach, acknowledging the need for intersectoral collaboration that “systematically takes into account the health implications of decisions, seeks synergies, and avoids harmful health impacts in order to improve population health and health equity” [9]. Climate action requires collective effort on all levels of society, from grass-roots community initiatives to policy reforms on a national and international level.

Health in all policies approach in the National Health and Climate Strategy [2].

By recognising the climate crisis as a critical public health issue, acknowledging the co-benefits of environmentally sustainable solutions, enabling First Peoples leadership, and fostering collaboration across sectors and borders, we can pave the way for a sustainable and resilient future. The urgency is clear, and the solution lies in our collective commitment to safeguard both the health of our planet and its people.

Disclaimer: Views are those of individual authors and not those of ACHSM or management intern’s employers

References

- “COP28 Health Day,” Dec. 03, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2023/12/03/default-calendar/cop28-health-day

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care (AGDHAC), “Launch of Australia’s first National Health and Climate Strategy,” Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care, Dec. 04, 2023. Accessed: Dec. 11, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.health.gov.au/news/launch-of-australias-first-national-health-and-climate-strategy

- “Alliance for Transformative Action on Climate and Health,” May 30, 2023. https://www.who.int/initiatives/alliance-for-transformative-action-on-climate-and-health

- “Over 120 countries back COP28 UAE Climate and Health Declaration delivering breakthrough moment for health in climate talks.” https://www.cop28.com/en/news/2023/12/Health-Declaration-delivering-breakthrough-moment-for-health-in-climate-talks

- M. Romanello et al., “The 2023 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: the imperative for a health-centred response in a world facing irreversible harms,” The Lancet, Nov. 2023, doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(23)01859-7.

- “Climate Effects on Health,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Apr. 25, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/climateandhealth/effects/ (accessed Dec. 10, 2023).

- Lancet, “Health Day at COP28: a hard-won (partial) gain,” The Lancet, vol. 402, no. 10418, p. 2167, Dec. 2023, doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(23)02746-0.

- V. Matthews et al., “Justice, culture, and relationships: Australian Indigenous prescription for planetary health,” Science, vol. 381, no. 6658, pp. 636–641, Aug. 2023, doi: 10.1126/science.adh9949.

- “What you need to know about Health in All Policies: key messages.” https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/what-you-need-to-know-about-health-in-all-policies–key-messages